Last month’s flooding event was proof

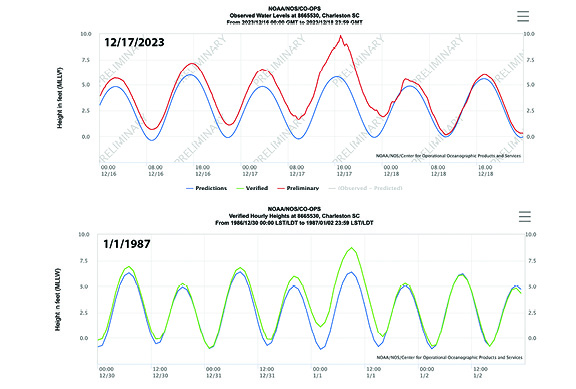

The morning of New Year’s Day, 1987, a wind-driven 8.81 tide sloshed waves across Arctic Avenue from numerous pocket beaches. At the washout, ocean water flowed across the road, through yards, then into the marsh on the backside of the island.

The morning of New Year’s Day, 1987, a wind-driven 8.81 tide sloshed waves across Arctic Avenue from numerous pocket beaches. At the washout, ocean water flowed across the road, through yards, then into the marsh on the backside of the island.

Later that morning, I walked down East Arctic from 6th block. Rubble covered the road near the pocket beach on East 5th Street. Next door, beach wrack covered the uneven concrete driveway between two yellow beach-cottages, where Bob and Carol Linville, Sally Beach, and O.D. once lived.

This extreme tide, the 2nd largest non-storm related-tide event on record, exposed some coastal vulnerabilities, prompting passage of The South Carolina Beachfront Management Act.

Eight years prior to the 1987 New Year’s Day storm, a study by coastal scientists Fitzgerald, Fico, and Hayes (1979) determined that the Charleston jetties restricted southbound coastal sand destined for Folly Island.

Since the Charleston Harbor jetties were found liable for (some of) Folly’s chronic erosion problem, Folly Beach was exempt from much of The Beachfront Management Act.

As a result of this exemption, those numerous pocket beaches mentioned earlier became homesites after beach renourishments started in 1993.

On Dec. 17, 2023 another huge tide event occurred. This marks the highest non-storm related tide event to date. At 9.86 feet, this tide is also the 4th largest tide on record in Charleston, including past hurricanes and tropical storms.

Though over a foot higher than the 1987 New Year’s Day tide, much of the island was protected by a substantial dune field created by numerous aforementioned beach renourishments. After hours of pounding surf, the big tide laid waste to some of the protective dune fields.

This most recent monster tide washed through several beach walk-overs and (again) across the road at The Washout, which is Folly Beach’s most vulnerable section along the island’s 6-mile strand.

The aptly-named “Washout,” a stretch of erosional beach from approximately East 14th block to East 16th block (plus or minus), is the location of a historical ephemeral tidal inlet between Folly Island and Little Folly Island.

The Washout is also a natural sediment bypass area that seldom accumulates enough dry sand to form protective dunes.

These two tides, occurring thirty-six years apart, may seem like freak occurrences, but this is less the case for the latter event.

In 1987, while early debates of human-driven climate change took place among academics, the general population wasn’t considering such vulnerabilities. Nowadays, the effects of climate change, including a warming earth and rising sea level, are coming at us like a locomotive down a tunnel.

To examine climate-related changes occurring in the coastal environment, let’s look at the data. According to the National Weather Service Coastal Flooding Database, high tide in Charleston has exceeded 7.5 feet 257 times since 1921. Of those 257 tides exceeding 7.5 feet, 171 (67%) of them have occurred since 2010.

In addition, High tide has exceeded 8 feet 48 times since 1921. Of those 48 tides above 8 feet, 35 (73%) of them have occurred since 2010.

Since 1921, the top ten 7.5-foot and 8-foot tide exceedance years happen to be the last ten years. There’s a trend here.

To put things in perspective, Charleston and Folly Beach high tides between 5.5 and 6.5 feet are considered “normal,” depending on the moon phase.

One long-time local made this telling observation: “Twice my yard has flooded from high tides in the quarter century since I’ve lived here. Both were this year.”

The data don’t lie. It’s reasonable to expect tides to keep getting higher. Tolerance of increased coastal flooding may be the price of living in Paradise.

Captain Anton DuMars, a coastal scientist and longtime Folly resident, listens to the science. To contact Anton, visit saltmarshdiaries.com and email him at saltmarshdiaries@gmail.com.